PAMELA MCCOURT FRANCESCONE

1) When and where was perspective born and what did it mean for painting and for art in general?

Linear geometric perspective was invented by the Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi sometime around 1425. This system for precisely representing the material world as seen from a single point-of-view in space and time was then codified by Leon Battista Alberti in his highly influential book Della pittura (On Painting) which was published in 1435. While the ancient Romans had created mosaics and murals showing three dimensional material objects in three dimensional space, as had the great Florentine painter Giotto early in the fourteenth century, linear geometric perspective made it possible, for the first time in history, for an artist to accurately show the things of the physical world at the same scale and in the same all-containing, homogeneous and infinitely extendable space. Perspective revolutionized art and architecture, and even Western civilization altogether, for the next five hundred years, contributing to the rise of Cartesian science, Enlightenment Reason and the modern culture of secular humanism.

2) What does Adi Da Samraj?s aperspectival art owe to the birth of perspective?

As Adi Da says in his book Aesthetic Ecstasy, the paradoxical space of his images is ?not Alberti?s kind of space, not the traditional space of Western art ? which (first) ?objectifies? the surface of the artwork, and (then) uses various devices to draw the ?viewer? into the ?objectified? surface.? Whereas perspectival art, by intention and design, reinforces the viewer?s sense of being a separate self looking, as if through a window, at a separate, objectively real world, Adi Da?s aperspectival art is made with the intention of undermining all efforts of the viewer to perceive it from any privileged point-of-view. In this sense, then, Adi Da?s art is an inversion of the ego, or self-reinforcing method and effect of perspectival art.

3) And to other great artists, past and present?

At the beginning of the twentieth century Braque and Picasso broke with the tradition of perspectival representation that started in Renaissance Italy, to produce Cubist paintings that portrayed objects from multiple perspectives simultaneously. Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian and other painters began to free themselves entirely from the need to represent objects as they appear to the eye in order to create a radically new abstract art.

Adi Da greatly values and praises the ideas, intentions and works of many of these artists, citing, in particular, the seminal contributions of Cezanne in the nineteenth century. He notes, however, that the aperspectival revolution that began with the artists of the last century ultimately failed to liberate humankind from the ?point-of-view?-based limits of either artistic representation or ordinary human perception. Rather, and somewhat ironically, the modernist revolution in the arts merely helped to create our own relativistic postmodern world, which accepts the presence of multiple points of view yet fails to experience or even acknowledge any reality that transcends it.

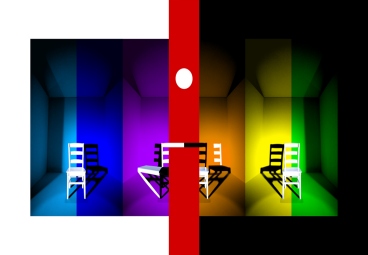

By means of his own aperspectival art which he has created over the past forty years, ranging from his Zen-like brush paintings and multiple exposure photography to his current work with monumentally scaled abstract geometric images generated by digital means, Adi Da has been striving to complete the modernist artistic revolution begun some one hundred years ago. His aim is to create images which enable the viewer to directly experience the transcendental reality that he asserts ?always already exists? prior to the dualistic experience of being a separate self perceiving a separate world.

4) How does his art, which he describes as “transcendental realism,” relate to Ghirlandaio?s fresco, The Last Supper? Is one the antithesis of the other?

By exhibiting four pieces of Adi Da?s monumental aperspectival geometric art in the same space that contains Domenico Ghirlandaio?s superb fresco of The Last Supper (1480), it is possible for visitors to experience the best of the perspectival art of the Renaissance as well as the aperspectival art of what the Swiss cultural historian Jean Gebser in 1933 called the emerging age of the ?Aperspectival/Integral Consciousness Structure?.

As Dr. Cristina Acidini, Superintendent for the Association of Museums of the City of Florence, rightly observes, however, these two radically different forms of art which are present together in the Cenaloco di Ognissanti, are held in dialectical embrace by a deeper, underlying unity: ??the secret and subtle alliance between these two different artistic expressions, based on the same principles of harmony and purity, turns this (dialectical) tension into an attraction to be enjoyed as a successful experiment.?

5) Adi Da Samraj says “the living body inherently wants to realise (or be one with) the matrix of life.” Is this a necessary state to be able to appreciate art? And what is there in Adi Da?s works that can help the viewer to attain, or strive towards, this state?

There are, of course, many worthy purposes for art, and many ways for different people to appreciate any given work of art at any given moment in time. Thus, a visitor to the exhibition in Florence might choose to simply enjoy the vivid colors, bold geometries and technical mastery evident in Adi Da?s images, without looking for any deeper experience or meaning. Or, another visitor might try to discover the various systems of geometry and color that give Adi Da?s images a mysterious sense of creative order. An art historian, on the other hand, might be satisfied to merely note the similarity between any one or all of Adi Da?s images to formally similar works by earlier artists of the modern era.

If, however, the viewer wants to experience all that Adi Da is offering by means of his art, it is necessary to grant it sufficient time and appropriate attention. As he says, ?right and true art ? speaks to silence, in silence ?.? Thus, after one has finally stopped trying to describe, categorize, or otherwise figure out any given image, one should simply relax, ?de-focus? one?s attention and, as he says in his book Transcendental Realism, ?simply participate in the images, by means of unguarded feeling-perception.?

There are at least two qualities to Adi Da?s art which support the possibility for this kind of aesthetic experience. Firstly, his images have a complex, aperspectival morphology, or formal structure, which does not allow the viewer to experience them from any conventional ?point-of-view?. As a result it becomes easy, and indeed necessary at some point, to surrender one?s attention to the images and simply wander ?mindlessly? within them. Secondly, his images are exhibited at a monumental scale, which makes it difficult, if not impossible, for the viewer to see any of them by means of a single controlling glance. Rather than beholding Adi Da?s images, one is beheld by them. Thus, by both of these formal means Adi Da?s images help us to lose ourselves in the spaceless spaces which are created by their pure, vivid colors and their playful geometries.

And, finally, it must be said that the artist Adi Da Samraj?s experience as a spiritual teacher who has undergone an intensive lifelong spiritual process, is inevitably expressed through the art he creates. In fact, he says that ?Reality Itself? is the state he communicates directly and wordlessly through his images. So, as Adi Da states, the reward for entering deeply into his images can be a potentially life-changing aesthetic experience: ?Ultimately, when ?point-of-view? is transcended, there is no longer any ?room? (or any separate ?location? and separate ?self?) at all?-but only Love-Bliss-?Brightness?, limitlessly felt, in vast unpatterned Joy.?