TERESA CARRUBBA

Frivolous, romantic, prim, austere or practical, in the choice of her wedding dress the bride expresses her intimate inclinations. And her taste. But it has not always been like this. In the past wedding dress traditions dictated more symbolic than aesthetic characteristics. In ancient Rome the bride?s simplicity and purity were expressed by her white tunic, the recta or regilla, with its essential lines, which was made from a vertically-striped fabric and worn with a bright red veil, the flammeum, which covered her hair, ritually divided into six plaits, and also her face which had to remain hidden from everyone except her ?betrothed.? The opulent era of Augustus introduced precious touches even on wedding gowns which sparkled with elaborate embroidery. As did those of Christian women, notwithstanding the severe lessons in sobriety given by Saint Augustine. The Barbarian invasion complicated both the ethos and the traditions of the day with repercussions also on fashion. The austere and solemn lines of the Roman wedding dress did not change, but the colours took on softer hues: blue, pink and violet, toning down the sharp white, gold and red shades which had been popular up to then. However, crimson continued to be used for bridal tunics throughout the Middle East for various centuries.

Even in Byzantium, where precious materials were taken into special account, and were embellished with every kind of stone. Crimson and gold were also used by Hebrew brides. This combination of white and red seemed to evoke, according to the symbology of the time, the fascinating amalgam of that purity and passion which was stirring in the soul of the bride and groom.

In the nineteenth century bridal white became fashionable in aristocratic and bourgeois marriages: white broken only by gold and silver trimmings in French Empire style. These were less popular with the lower classes who preferred the more gaudy crimson or black with coloured woollen embroidery and worn with a white shawl. The aristocratic classes also favoured black for the civil ceremony but it sparkled with sequins, while pastel colours (with pink being the most popular) lavishly embroidered with pearls and sequins were worn for the signing of the marriage portion contract. But above and beyond the allegorical connotations of the colours which remained significant down the centuries, the style of the wedding dress was a way of identifying the elements which characterised the mores of the time conditioned, as they were, by the different historical and social situations. The train was introduced in the 13th century, an era of thriving commerce and which saw appearance of the bourgeoisie, and down the centuries it remained the most important element of the wedding dress.

The longer it was and the more material it took the more indicative it was of wealth and social prestige. The sleeves, which were skin-tight thanks to the introduction of buttons, were lavishly embroidered and set with precious stones. And as if this was not enough the bride, especially if she was a noble bride, also wore elaborate belts and diadems. As in the case of Isabel of Aragon who, for her marriage to Gian Galeazzo Sforza, wore a dress in heavy gold brocade and on her head wore a large crown which was overly encrusted with pearls.

The luxurious tastes of brides from the noble classes lasted down the centuries and became even more marked in the late 13th century when regal mantles, lined with expensive furs like ermine, became popular. In the 15th century Nannina de? Medici married Bernardo Rucellai, wearing a pompous wedding dress made of a flowery gold and white damask brocade with sleeves entirely covered with pearls. And Bianca Maria Sforza, the niece of Ludovico il Moro, who married the Emperor Maximilian of Austria, wore a rare crimson satin embroidered wedding dress embellished with golden rays with a bodice studded with gems, enormous winged sleeves, an extremely long train and she wore diamonds and pearls in her hair. But it was Beatrice d?Este who dictated fashion trends in the 15th century, wearing dresses she had designed herself in an ongoing duel with her sister Isabella. Lucrezia Borgia was another woman who had original and magnificent tastes: wrongly famous only for her intregues and poisons, she also left her mark on fashion. And when it came to wedding dresses she was something of an expert as she married three times. When she married Giovanni Sforza, Count of Codignola (1493), she wore a gold and silver brocade dress with a showy train and she covered herself with jewels. In 1498, she married Alfonso of Aragon, the natural son of the King of Naples and then, in 1502, for the third time she married Ercole the Duke of Ferrara, wearing a truly spectacular dress: a series of satin, velvet and brocade skirts worn one over the other, a tunic lined with ermine and an over-vest in gold brocade. On her hair she wore a gold cap embroidered with rubies and diamonds, with more of the same around her neck. In the 17th century, dominated by Baroque, wedding dresses were inspired by the Spanish faldia which had a narrow girdle, nipped in with bands, whalebone or other similar ?instruments of torture.?

This was also the era of transparent blouses (to the indignation of Pope Innocent XI who ordered them to be impounded in laundries) and of seductive décolletés embellished with lace or light and elaborately embroidered materials, the so-called fishu which were so fashionable at the end of the 19th century. The creation of a square neckline, bordered with a pleated collar around the shoulders, which were left bare, has been attributed to Maria de? Medici and it brought a strong reaction from the Church on the occasion of her proxy marriage to Henry IV, King of France. The 18th-century wedding dress, on the other hand, was influenced by the French Baroque, Rococo and neo-Classical styles. And while considered too ?uninhibited? the andrienne, a very tight dress with a plunging neckline and a long cape with a train, became highly popular and was chosen by Charlotte Aglae of Orléans, the French regent, for her wedding in Modena (1720) to Rinaldo d?Este. The Rococo style introduced tiny flowers and pastel coloured satin, velvet and taffeta, while neo-Classical suggestions triumphed in the austere ?Empire style? after Napoleon?s victories culminating in the wedding of Maria Luisa of Austria, regally arrayed in symbolic white with gold decorations and with a purple mantle lined with ermine. The apotheosis of the wedding dress, seen as the expression of solemnity, was reached in the 19th century. Elisabeth of Baviera (better known as the Princess Sissi) led fashion in the second half of the 19th century and, for her marriage to Franz Joseph, the Emperor of Austria (1854), chose an antique moiré dress, generously embroidered with gold and silver and embellished with myrtle.

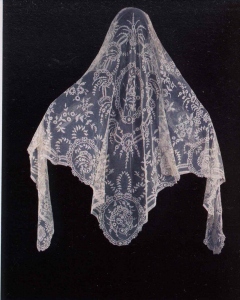

It had an underskirt held up with whalebone and a heavy mantle with a train which was embroidered with gold and fixed to her shoulders with splendid diamond clips. But the apex of pomposity was certainly the dress which Margherita of Savoy wore for her wedding to her cousin Umberto, the son of Vittorio Emanuele II. For the occasion the eccentric and ostentatious Queen Margherita choose a dress covered with daisies, roses and orange blossoms (made from wax), festoons of bells, bows, flounces, embroidery and lace. All of which was ?lightened? by a mantle which was three meters and sixty centimetres long. However Queen Margherita did boost the production of laces and actively supported the School of Lace and Needle in Burano which also made highly refined decorations, under the queen?s watchful eye. Some of these embellished the wedding dress of Princess Elena of Montenegro, the wife of the future King Vittorio Emanuele III. At the turn of the nineteenth century fashion reached new heights thanks to Worth, the Parisian tailor who counted empresses and noblewomen among his clients. Then the First World War put an end to these elaborate and showy types of fashion, imposing simpler, more elegant and essential styles.