JUSTIN CORFIELD

Harold Sterling Vanderbilt, railroad magnate, three times the skipper of a winning yacht in the Americas cup, and great-grandson of the noted financier Commodore Vanderbilt, invented Contract Bridge along with three others aboard the steamship Finland in 1925, somewhere between Los Angeles and Havana, quite possibly whilst passing through the Panama Canal.

Contract Bridge was Vanderbilt?s improvement on the earlier game of Auction Bridge, which had been around for some 75 years previously, itself a development of the game of Whist, which had been around for longer still. Playing cards, of one form or another, have been with us for well over a thousand years.

Like Whist, the game of Bridge revolves around the taking of ?tricks? – one player leads a card (places it face up on the table), and then each of the others must play a card of the same suit, going clockwise around the table until all four players have played. Whoever played the highest card of the suit that was led wins that trick, and leads to the next one.

Bridge is played in partnerships, two pairs playing against each other. North and South sit opposite each other, and play against ?East-West?. A standard deck of 52 cards is dealt, giving each player 13 cards, and so there are 13 tricks to be won on each deal. Once the cards are dealt, an ?auction? follows, in which both sides compete for the right to designate what suit will be ?trumps? (if you cannot follow suit on a given trick, you can play a trump, which beats all other cards except a higher trump). In this auction, the players make ?bids? which say that their combined side will make a specified number of tricks if a particular suit is trumps. The side that makes the highest bid then has to try to make the number of tricks they contracted to make, whilst the other side try to stop them.

The first player who bid the eventual trump suit becomes ?declarer?, and plays both his or her own cards, and those of their partner, all of which are placed face up on the table, known as the ?dummy? hand.

Put like that, the game might seem rather dull, but let me assure you that it is not. Most competitive bridge is played as ?duplicate? bridge, which means that the same hands are played at a number of tables. To win at this form of bridge requires that you do better than other people who have the same cards as you do ? in other words, luck has very little to do with it.

Chess is the only game that can possibly compete with bridge on an intellectual level, and I wouldn?t like to bet on which is the harder game to master, in the unlikely event that anybody truly masters either. Samuel Reshevsky, the US chess champion, decided to become an expert at Bridge too, but despite devoting all of his time to it, he ended up finding the game too difficult. Other famous Chess players have been keen Bridge players as well, including the legendary players José Raŭl Capablanca, and Emanuel Lasker.

Bridge contains many unfathomable subtleties, and has a habit of very quickly getting ?into the blood? of those that play it, to the extent that they, or should I say ?we?, can think about little else.

Amunallah II, the Emir of Afghanistan, 1919-29, was so obsessed with the game that he had to abdicate his reign. The depiction of the human form was considered a sacrilege by orthodox Muslims, and the Queens on playing cards wear no veils. It was down to those four Queens that Amunallah II was ousted from his rule.

He wasn?t the only famous or influential person to fall under the spell of bridge. President Eisenhower was a very keen player, and regularly held games in the White House. He used bridge for relaxation, and was playing a famous game while he waited to hear news of the Allied landing in Casablanca. Eisenhower was a strong player, and a hand he played was reported by Oswald Jacoby, a legend of the game, in the New York Times.

Show business personalities are not immune to the allure of the devil?s picture book either. The Marx brothers were fanatically keen on the game. Omar Sharif has been an ambassador for bridge for years, and is an exceptionally talented player, having represented his native Egypt internationally. Rumour has it that he first learned to play on the set of Lawrence of Arabia, whilst waiting for the many extras to be kitted out.

James Bond?s creator, Ian Fleming, was another person to succumb to the game of bridge, and it features in many of his novels. In the famous scene where Goldfinger plans to slice Bond in half with a laser (a buzz saw in the novel ? lasers didn?t yet exist), Bond stops him by telling him that he knows about ?operation grand slam?. A ?grand slam? in Bridge is where one side contracts to make all thirteen tricks.

The comedian George Burns played bridge regularly right up to the time of his death, aged 100.

And that is a part of the appeal of the game. All ages can play. Boris Schapiro, a British player of Russian extraction, won the Gold Cup ? a very prestigious event, at the remarkable age of 88 (some 52 years after his first win)! The next year, he went on to win the World seniors Pairs Championship, now at a youthful 89. In what other sort of competition or game can somebody of such an age even compete, let alone win?

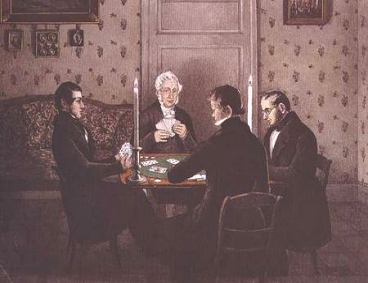

But in bridge, age matters not. Neither does race, religion, gender, nationality, wealth or anything else. I have seen many games of bridge played by four people who have nothing in common at all. Sometimes, the players have hilariously opposing views on virtually everything. Picture Amunallah II, Dwight D Eisenhower, Groucho Marx and Ian Fleming playing a few hands together, and you?ll see what I mean. Such a pity they didn?t ? I would have loved to see that particular game unfolding.

Over the last century, Bridge has been the setting for some very strange happenings.

Take the unfortunate case of Harry Meacham, of North Carolina. Meacham was having a terrible run of luck in a high stakes bridge game, and announced that he would shoot the next person who dealt him poor cards. He promptly dealt himself a bad hand, put a gun to his head, and shot himself dead, to the stunned silence of the other people in the room.

Then there was the even stranger case of John and Myrtle Bennett, of Kansas. Playing a ?friendly? game of bridge against their neighbours, Mr Bennett became the declarer, and to succeed in his contract he had to take ten tricks, with spades as trumps. When he failed to do so, his wife shot him dead, telling their neighbours that he was a ?bum bridge player?. She was later miraculously acquitted in court (the jury deciding that the shooting was accidental), and collected on her husband?s substantial life insurance policy. Perhaps a few jurors were bridge players too, and sympathized with her plight.

One of my favourite bridge-related anecdotes concerns the Indian player, Om Parkash Chaudhry. Completely blind, he used to play by having another person sit next to him, and whisper to him what cards he held. One day Chaudhry was playing in a tournament in India when suddenly there was a power cut and the lights went out. Chaudhry just continued playing, unaware that anything was amiss. When somebody explained that the other players couldn?t play without being able to see their cards, he was surprised, having forgotten that other players actually needed to see!

Bridge is played today all over the world. The smallest games of bridge consist of four players around a kitchen table, whilst the biggest tournaments have hundreds of tables, sometimes thousands, all playing the same hands, generally located in very upmarket hotels and casinos. I have played in bridge games that started at 7.00am, and ones that started at midnight. Anybody can play bridge, anywhere.

The last time I played bridge online, the website in question had over thirteen thousand people playing at that moment. For some of us it was ten o?clock at night, for others it was four in the morning. It really doesn?t matter, the game?s the thing. Multiply that thirteen thousand by the number of websites devoted to bridge (lots of them), and you get some inkling of just how popular and addictive this game can be. My guess is that you could add together the number of people playing football, cricket and rugby right now, at this moment, and it would be nowhere near the number currently playing bridge. Many people interested in sports enjoy watching them, either going to the game or watching on television, but do not play themselves, at least not often. People interested in bridge invariably do play it themselves. Any highs or lows we bridge players get from the game are the results of our own efforts, which is quite different to feeling emotionally attached to a team of which we are not members.

Some people play bridge for money, known as ?rubber? bridge.

Others play in clubs and tournaments, whereby they hope to acquire ?masterpoints? – as the total number of points you have increases, you go up the ranks, ?grand master? being the highest.

Some of us just love the elegant, abstract nature of the game. Occasionally, just very occasionally, a bridge player gets the chance to play a really difficult hand, where the contract can only be made by producing a work of art. There are many spectacular ?coups? possible in bridge, both for the side declaring and for the side defending. It is not easy to explain to the non-player what these masterpieces are all about, but it resembles the situation in chess where sometimes a player can seemingly sacrifice most of his pieces, but the result is that the opponent is checkmated.

And some just play for sheer enjoyment and the social nature of the game. Bridge is all about partnership, and being able to work together with somebody else to achieve some goal. Bridge partnerships are rather like marriages ? some are very long-lasting and monogamous, whilst others ?swing? quite cheerfully. It won?t surprise you to learn that I know many bridge players whose bridge partnerships have survived intact for dozens of years, but whose many attempts at marriage have been, shall we say, rather less successful.

Bridge is not a game for the recluse, the isolated genius who emerges after years of study to gain world dominance. You can only win or lose at bridge as one half of a partnership that has won or lost, and so to succeed requires that you think like a partnership. As you might imagine, this involves a lot of psychology, guesswork, trust, intuition? To be successful in bridge, a player has to be able to get the best out of their partner, and this is not always easy. Sometimes, if one?s bridge partner makes a horrible mistake, it is very hard not to say something apposite to them, in front of your opponents. But the psychology of the game adds to its depth and complexity. No amount of knowledge about how to play cards is of any use to somebody who doesn?t understand enough about people. And yes, I know plenty of players who fall into that category too.

I am sure that at one time or another you have sat in a car, stuck in the mother of all traffic jams, and wondered what the inventor of the car would make of all this if only he could see it today. When I play in a big bridge tournament, where as far as the eye can see all you have is bridge table after bridge table after bridge table, I wonder what Harold Vanderbilt would make of it all if only he could see it. There are well over 30 million bridge players in the US alone, and many, many more worldwide. I don?t think Harold would have believed it.

I shall leave you with a famous hand:

North / dummy / ?M?

♠ 10 9 8 7

♥ 6 5 4 3

♦ -

♣ 7 6 5 3 2

West / Meyer East / Drax

♠ 6 5 4 3 2 ♠ A K Q J

♥ 10 9 8 7 2 ♥ A K Q J

♦ J 10 9 ♦ A K

♣ - ♣ K J 9

South / declarer / Bond / 007

♠ -

♥ -

♦ Q 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

♣ A Q 10 8 4

In the novel ?Moonraker? Bond rigs a bridge hand against the villainous Drax.

Bond, sitting South, and of course knowing all four hands because he has fixed the deck, bids 7♣, a grand slam, saying that his side will take all thirteen tricks if clubs are trumps. Drax, sitting East, doubles this (effectively offering odds that declarer will not succeed), and Bond redoubles. The stakes, now, are enormous. Despite Bond having virtually no high cards at all, there is no way for the defenders to defeat 7♣, as declarer can trump two diamonds in the north hand, establishing the suit, whilst leading through East?s clubs twice. If instead East had bid 7♥ or 7♠, a diamond lead from South would allow North to score a trump trick, defeating the grand slam.

If West had somehow managed to bid 7♥ or 7♠, though, he would have succeeded. Doubtless Drax pointed that out to Meyer after the game.